PAUL T. SHIPALE (with inputs by Folito Nghitongovali Diawara Gaspar)

Abstract

This article critically examines the constitutional status of Namibia’s Leader of the Official Opposition, a position declared unconstitutional by Panduleni Itula of the Independent Patriots for Change (IPC). Employing a dialectical analysis (thesis-antithesis-synthesis), the study explores the tension between statutory deficiencies and parliamentary conventions that underpin the office. By situating Namibia’s semi-presidential hybrid system within a global comparative framework, including France and Zambia, the article argues that, while the role lacks constitutional grounding, its functional necessity in a democratic system warrants formal legislative codification. It concludes with recommendations for constitutional amendments to solidify the opposition’s powers, ensuring greater accountability and institutional stability.

Keywords: Official opposition, semi-presidentialism, constitutional reform, Namibia, parliamentary conventions, hybrid governance.

I. Introduction

The position of Namibia’s Leader of the Official Opposition has become a point of contention in the country’s democratic discourse. IPC leader Panduleni Itula criticized the office as unconstitutional, asserting that it was established through executive proclamation rather than a legislative process. This challenge raises fundamental questions about the role of parliamentary conventions in the absence of formal constitutional recognition. How do hybrid governance systems balance executive authority with the accountability of the opposition? This article explores Namibia’s unique situation, drawing from comparative legal theory and political practice, while proposing reforms to address the gaps between statutory limitations and democratic imperatives.

II. The Thesis: Statutory Deficiencies and Democratic Erosion

1. Executive Proclamation vs. Constitutional Legitimacy

The office of the Leader of the Official Opposition was created in 2020 by the Late President Hage Geingob, providing privileges such as security, vehicles, and staff, but without a statutory or constitutional foundation. Itula’s characterization of the office as a “shadow with a salary” underscores its vulnerability to political manipulation, as its existence is governed by parliamentary standing rules, rather than clear constitutional or legal mandate.

2. Parliamentary Rules as Fragile Foundations

The Amendment of the Namibian Constitution with the inserted Article 73A grants parliament the right to regulate its procedures, but parliamentary conventions, such as those governing the opposition leader’s privileges, remain susceptible to change. Itula argues that the 2020 Government Gazette prioritized benefits over the codification of responsibilities, leaving the position in a state of legal uncertainty.

3. Comparative Precedent: The Westminster Model

In comparison, the UK’s Ministers of the Crown Act 1937 (1 Edw. 8. & 1 Geo. 6.c. 38) was a landmark piece of legislation that formally recognized the Prime Minister, the Cabinet, and the Leader of the Opposition, setting salaries for government opposition members, and simplifying law as regarding parliamentary participation of those holding government offices. Thus, it formally recognized opposition leaders, ensuring their institutional legitimacy (May, 2019).

III. The Antithesis: Conventions, Functionality, and Political Realities

1. The Necessity of Parliamentary Pragmatism

Critics, including McHenry Venaani of the Popular Democratic Movement (PDM), argue that many parliamentary roles (e.g., party whips) are derived from convention rather than constitutional mandate. In this context, the opposition leader’s de facto importance in holding the government to account justifies the role’s existence, even if it is not legally codified.

2. Internal Party Dynamics and Power Struggles

Some analysts (Kamwanyah and Tyitende) argue that Itula’s opposition to the office arises from concerns over intra-party power dynamics. The position of opposition leader would empower the parliamentary leader of the IPC, potentially sidelining Itula, who is not a member of parliament. This reflects broader tensions over political control within the party.

3. Contradictions in the Shadow Cabinet

Itula’s creation of a shadow cabinet—similarly not constitutionally recognized—reveals an inherent contradiction. As Tyitende observes, “One cannot critique illegitimacy while replicating it”. This inconsistency exposes the complexity of political maneuvering in the absence of clear legal frameworks.

IV. Synthesis: Toward a Codified Legitimacy in Hybrid Systems

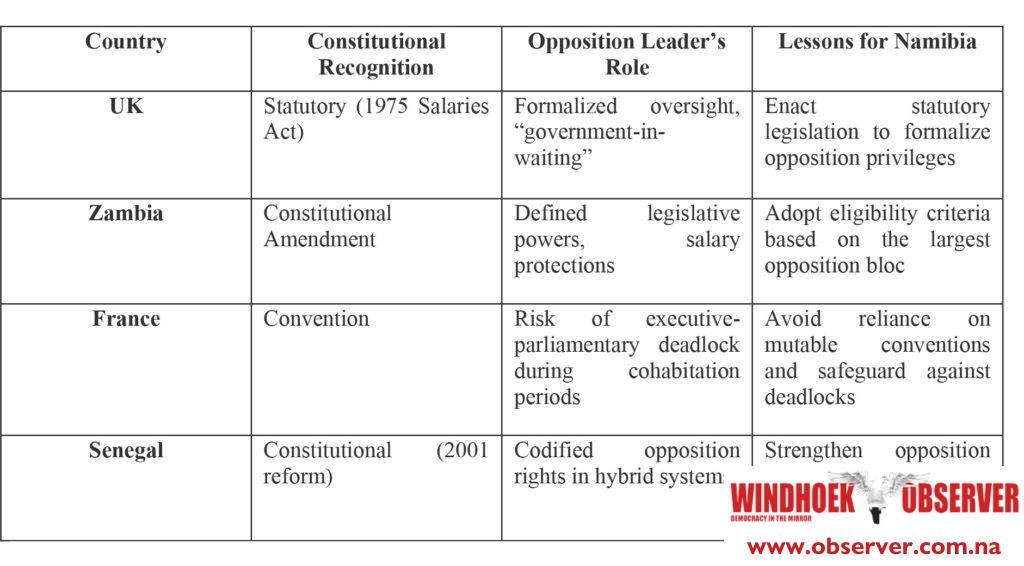

1. Lessons from Semi-Presidential Systems

Namibia’s political system combines a directly elected president with a prime minister accountable to parliament (Duverger, 1980). Unlike France’s cohabitation model, where the president and prime minister share executive powers, Namibia’s president retains dissolution powers, creating asymmetries. Comparative models, such as Zambia’s Constitution, offer valuable insights. In Zambia, opposition leaders are drawn from the largest opposition bloc in parliament, with defined powers and protections.

2. The Case for Constitutional Amendment

While parliamentary conventions can function in stable democracies, Namibia’s nascent political institutions require greater clarity. A constitutional amendment could:

• Establish clear eligibility criteria for the opposition leader (e.g., membership in parliament).

• Specify powers, such as the ability to scrutinize the budget and lead parliamentary committees.

• Safeguard the position from arbitrary revocation.

3. Mitigating the Risks of Hybridity

The cohabitation crises in France (1993, 1997) illustrate the risks of unchecked executive-legislative rivalry. Codifying the opposition leader’s role in Namibia would mitigate such risks, ensuring a more balanced hybrid system. Senegal’s 2001 reforms (Diop, 2020) provide a relevant example of successfully balancing presidential power with opposition rights.

V. Conclusion & Recommendations

Itula’s critique exposes a significant democratic deficit in Namibia: the lack of constitutional recognition for the opposition leader. Although parliamentary conventions have sustained the role, their fragility in a hybrid governance system necessitates reform. Codifying the opposition leader’s role would align Namibia with global best practices, ensuring both accountability and the protection of minority rights.

Maybe it is high time for Parliament to introduce an Opposition Accountability Act to establish resources, staffing, and procedural authority for the role of the leader of the official opposition in Namibia, specifying eligibility and delineating oversight powers in order to formalise it?

Otherwise, as the Landless People’s Movement leader Bernadus Swaartbooi has expressed his concern on the possibility of there being no official opposition leader in Parliament, the next five years of the 8th Parliament would be challenging if the title is not assigned de jure in the National Assembly as there would only be de facto leaders having their field day because the IPC leader Itula said that his party would not accept the position of leader of the official opposition in the National Assembly, despite his party holding twenty seats in Parliament. Indeed, Panduleni Itula, the leader of the Independent Patriots for Change, has shot himself in the foot. Tough luck to him.

VI. Appendix 1- Global Comparative Analysis

VII- References/Bibliography

Donald Matthys, ‘Itula calls for stronger official opposition powers in Namibia’, The Namibian Newspaper, 01 April 2025

The Report, ‘IPC defectors exercised their democratic right: Nashinge’, New Era Newspaper, https://neweralive.na, 02 April 2025

Lahja Nashuuta, ‘Itula ditches official opposition tag and declared it unconstitutional’, New Era Newspaper, 04 April 2025

Martin Endjala, ‘Itula’s IPC shadow cabinet: Strong on accountability, but absent in parliament’, The Namibian Newspaper, 06 April 2025

W. I. J., ‘The Ministers of the Crown Act, 1937’, The Modern Law Review, Vol. 1, No. 2 (Sep., 1937), https://www.jstor.org/stable/10902 Catherine Haddon Alice Lilly Jo-Anna Hagen Schuller, ‘Official opposition’, As the second largest party in the House of Commons, the Conservative party is the current official opposition, 06 July 2024, This explainer was originally published on 23 December 2020 Leaders of the opposition from 1807. (May 2014) Statutory leaders of the opposition from 1937: Erskine May: Parliamentary Practice Marcel Gauchet, Pierre Manent, Luc Ferry, and Alain Renaut, ‘New French Thought: Political Philosophy’, Originally published in 1994.

Levitsky and Way 2002: 54, ‘Political oppositions beyond liberal democracy: Some empirical features and patterns’

William Gumede 2017, ‘Policy Brief 45: The Role of Opposition Parties in Developing Democracies’

Keesing’s Contemporary Archives 1937–1940 (at 4069D) reported the situation, based on Hansard. Back to Business: Opposition parties, 3 Jul 2024.

Policy Brief 45: The Role of Opposition Parties in Developing Democracies William Gumede, ‘Opposition in a hybrid regime: The functions of opposition parties in Burkina Faso and Uganda. The nature of political opposition in contemporary electoral democracies and autocracies. Vulnerability to outsider challenges’ Grundholm 2020: 797, Levitsky and Way 2002: 54, Magaloni and Kricheli 2010: 126–128, Keane 2009: 853 Erskine May: Parliamentary Practice Ministers of the Crown Act 1937. Statutory leaders of the opposition from 1937 Keesing’s Contemporary Archives 1937–1940 (at paragraph 4069D)

The Daily Herald reported that the Parliamentary Labour Party met on 22 May 1940, Back to Business: Opposition parties, 3 Jul 2024

William Gumede, ‘Opposition in a hybrid regime: The functions of opposition parties in Burkina Faso and Uganda Policy Brief 45: The Role of Opposition Parties in Developing Democracies’ Gumede 2017, Bulmer 2021; Melber 2007, Robinson and Hoffman 2009; Wilks 2023; Mugabi 2023; Lemière 2020. Opposition Parties in Africa and Developing Countries