Moses Magadza

WINDHOEK – The COVID-19 global pandemic has amplified the need to address issues related to Intellectual Property (IP) and human rights as well as for taking steps to benefit from TRIPS flexibilities to ensure access to medicines for all.

As Least Developed Countries (LDCs) join the rest of the world in rolling out COVID-19 vaccines, there are concerns over access, transparency, equity and human rights violations. Against this backdrop, SADC Members of Parliament last week called for all hands on board to build the region’s capacity to produce medicines and to ensure that citizens benefit from their vast medicinal plant resources.

A joint session of the SADC Parliamentary Forum’s Standing Committees and the Regional Women’s Parliamentary Caucus called on SADC Member States to harness the “flexibilities afforded by Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights, to respond to their various communicable and non-communicable disease (NCD) public health concerns”.

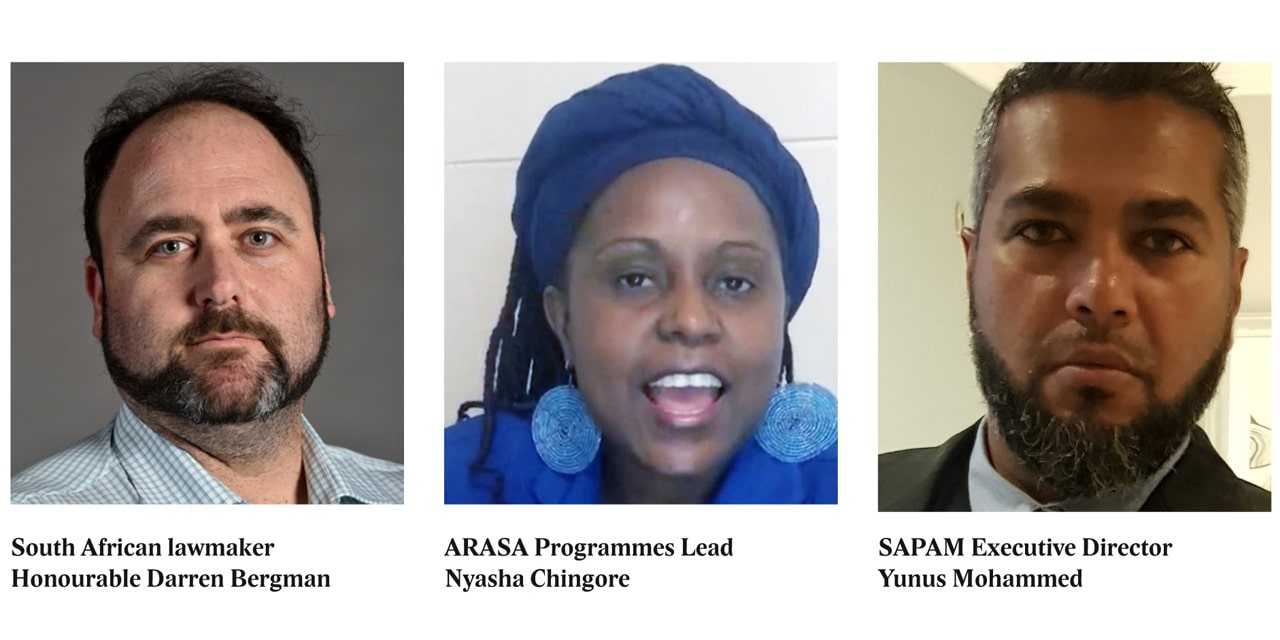

Their call followed advocacy presentations by the AIDS and Rights Alliance for Southern Africa (ARASA) and Southern African Programme on Access to Medicines and Diagnostics (SAPAM).

South African lawmaker Honourable Darren Bergman speaking on behalf of the Chairperson of the SADC PF Standing Committee on Democratisation, Governance and Human Rights expressed the SADC MPs’ call at the end of the virtual joint session. He said following the outbreak of COVID-19, and before it, HIV, TB, Malaria and other diseases, “providing equitable access to health, remains a challenge”.

He stressed the need for SADC MPs to “remain committed, and engaged, using the tools and resources available to focus on Intellectual Property Rights and their impacts on access to medicines”.

His remarks followed revelations by Ms Nyasha Chingore, the Programmes Lead at ARASA and Mr Yunus Mohammed, the Executive Director of SAPAM, that despite the existence of enabling flexibilities within TRIPS, Least Developed Countries (LDCs) in SADC were not exploiting them.

Furthermore, the duo noted that “the main challenge with IP rights and access to medicines in sub-Saharan Africa is the gap between the huge disease burden and the slow uptake of TRIPS flexibilities that are freely available to the countries” because of “structural and technical factors”.

They highlighted challenges thwarting domestication of TRIPS flexibilities which allow LDCs to override pharmaceutical patents for essential medicines in the public interest until 2033.

They include, “lack of understanding or appreciation of tangible benefits of TRIPS flexibilities; conflicting interests between industrial policy, public health and revenue collection; lack of clarity about which government agency takes responsibility or lead e.g. Health, Trade & Industry or Finance; national interest overriding potential benefits from regional cooperation e.g. lack of using LDC status for benefit of region; bilateral trade agreements negating benefits of TRIPS flexibilities e.g. TRIPS+ through bilateral trade agreements” and “apparent inertia in parliamentary processes in getting to Bill stage then Act of Parliament”.

In their joint presentation, the duo suggested increasing “understanding and appreciation to prioritise TRIPS flexibilities” and ensuring relevant Parliamentary Committees drive the “process of harnessing TRIPS flexibilities and pharmaceutical waivers”.

They recommended that “generic manufacturers” in LDCs “team up with experienced manufacturers for technology transfer to produce pharmaceuticals that meet WHO pre-qualification standards” as well as “strengthen linkages between tools in Pooled Procurement/Procurement Cooperation Strategy and Local Production to maximize TRIPS flexibilities implementation.”

Some of these strategies, they said, could include integrating to a price sharing medicines database, Pooled Procurement Network, and Regulatory and Review of Patent Legislation in the region” as well as patent pooling “where a patent holder shares his patent with several other manufacturers who are then allowed to make the drug for a small fee”.

They noted that these arrangements would not only promote the availability of locally manufactured generic drugs but also create jobs, value chains and downstream industries although they also acknowledged challenges such as suboptimal human resources, lack of coordinated policies, lack of locally available raw materials, high operating costs and technological inadequacies among other hindrances.

Furthermore, the ARASA and SAPAM representatives said that LDCs could avoid bilateral agreements that may limit benefits from TRIPS flexibilities and “strengthen harmonization/convergence efforts in pharmaceutical value chains of medicines registration, procurement and supply management standards and practices”.

They argued that the vaccine supply gaps in SADC show “the importance of epidemic preparedness” and the need to adopt “progressive IP policies” to ensure member states, “are able to leverage the TRIPS flexibilities as and when public health emergencies emerge”.

ARASA and SAPAM contend using the TRIPS flexibility window and capacitating regional manufacturing of generic drugs would allow SADC member states to address the African Union’s Agenda 2063 provision on improving the quality of life of citizens and achieving the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goal 3 which focuses on good health and wellbeing.

It became apparent during the meeting that Parliamentarians could continuously raise issues in parliament and use their oversight function to ensure that laws are actually implemented and resources budgeted for. It was suggested that MPs ensure that offices dealing with patent issues are manned by well-trained staff who understand the impact of IP on public health.

The SADC MPs’ call for action comes amid growing concern over lack of implementation of Intellectual Property Acts enacted between 2012 and 2020 by some SADC Member States. Chingore said four out of the 16 SADC Member States had enacted new IP/Patent legislations incorporating the TRIPS flexibilities. These are Botswana, Mozambique, Seychelles and Namibia.

“Eswatini and Zambia have pending implementation regulations for their IP Acts to be enforced. Madagascar and Mauritius developed draft IP Bills in 2016 and 2017 respectively, but these processes have stalled.” she said.

She explained that lack of implementing regulations, which administer and enforce the provisions of the law by providing practical interpretative guidance on how the law is to be applied, was one of the factors impeding implementation.

“For some countries, it takes years for implementing regulations to be developed and adopted. Namibia took six years to develop and consolidate implementing regulations to the Industrial Property Bill of 2012,” she said.

Similarly, Zambia enacted her Patent Act in 2016 but implementation has been stalled due to a lack of implementing regulations, leaving the country to rely on the Patents Act of 1958 (Chapter 400, as amended up to Act No. 13 of 1994).

In Eswatini, the Patent Act No 19 of 2018 is not yet in force due to outstanding regulations. The patent regime is governed by the Patents, Design and Trade Marks Act of 1936.

Chingore confirmed that there had been reports of COVID-19 related corruption and violation of human rights in different parts of the world.

“Examples include reported scandals in relation to the procurement of PPE (Personal Protection Equipment) and COVID-19 test kits. In the context of vaccines, transparency sometimes lacks around conditions of bi-lateral agreements with suppliers,” she said.

Elsewhere, officials have created the impression that they intended to make vaccination mandatory.

“This is unfortunate as informed consent is critical to ensuring buy-in. Vaccine programmes should also ensure that they are not solely centered in urban centers and that there is no discrimination on the basis of geographical location or social or economic status,” she said.