Moses Magadza

As stories of the shenanigans of some lawyers all over the world continue to feature in the media with monotonous regularity and threaten to put their profession into disrepute, Lawyers, a book by a widely acclaimed legal expert, has come out to discuss ethical obligations of lawyers and say what ought to be the standard.

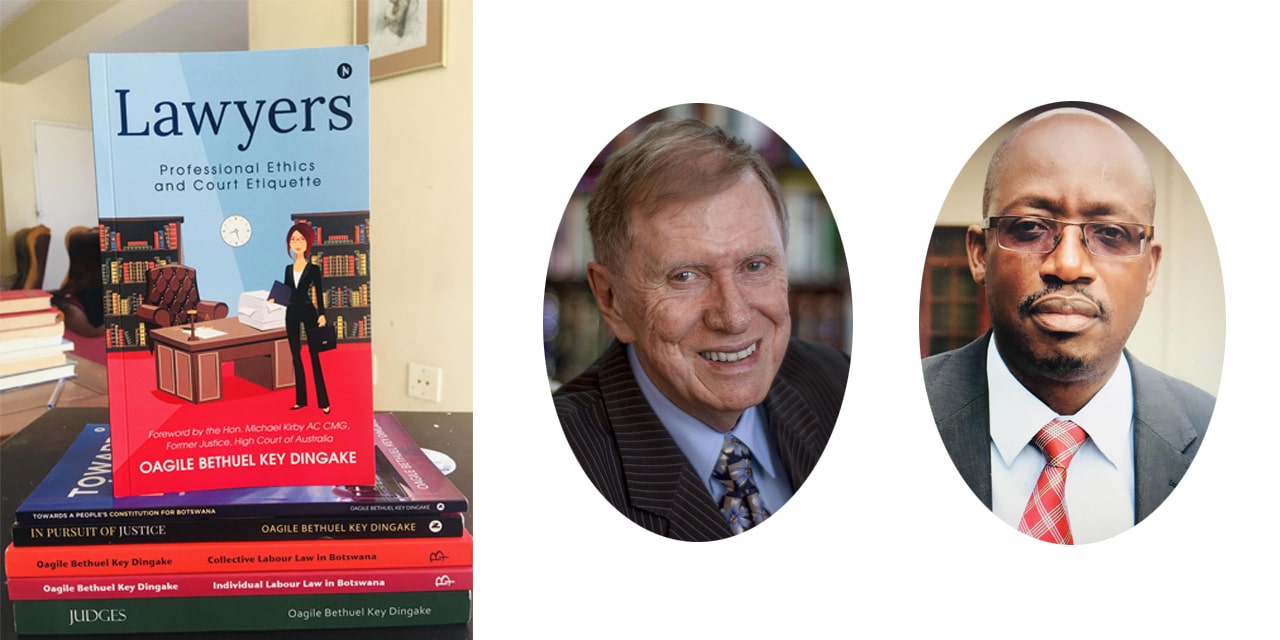

The author, Justice Professor Oagile Bethuel Key Dingake, is a former Judge of the High Court of Botswana, a Justice of the Residual Special Court of Sierra Leone, former Judge of the Supreme Court of Papua New Guinea and now with the Court of Appeal of Seychelles. Lawyers was published last year.

It joined three other law books which Dingake published the same year: In Pursuit of Justice, Judges, and Towards a People’s Constitution for Botswana. In all, Dingake has published nearly 10 books and numerous peer-reviewed articles in rapid succession. This is a remarkable feat for a busy full-time judge.

Notion Press of India published Lawyers to wide acclaim. A renowned former Justice of the High Court of Australia, Justice Michael Kirby AC CMG, wrote the foreword. In it, the learned judge recommends the book to all “lawyers across the globe”.

Like other books before it, Lawyers is written in accessible English and is brief. Indeed, brevity and simplicity define Dingake’s writing style. Reading it, I was reminded of the importance of lawyers in every society. In many societies, lawyers are revered or derided, in equal measure. Those who hold them in high regard and look at them through rose-coloured spectacles believe that lawyers belong to a noble profession committed to truth, justice and nothing else. This is what Dingake says lawyers ought to be in this fascinating book.

However, in fairness, Dingake concedes early in this book, that of recent the legal profession has begun to show signs of decay and has fallen short of being a noble one, in terms of etiquette and ethical obligations. He argues that lawyers must never be emotive about their client’s case and that they must always be respectful to the court, its staff and fellow lawyers.

This reminded me of a recent incident in South Africa involving a top Advocate who set tongues wagging when he sensationally ordered his erudite colleague to “shut up”. This conduct was sharply rebuked by the presiding judge as unacceptable in the legal profession. The judge was almost echoing the golden line that runs through this book – that lawyers must remain professional and measured even under extreme provocation.

As intimated above, Dingake bemoans the fact that of recent across the globe, the legal profession has seen many instances of deterioration in standards. Parts of the general public complains are to do with lawyers who do not apply themselves adequately to the legal issues serving the court. In extreme cases some lawyers have faced accusations of misappropriating client’s funds or poorly managing trust funds.

Dingake urges a return to the ethics of what he describes as “the noble profession”. He writes that lawyers should not engage in conduct which is dishonest or unbecoming or which may cast doubt on the lawyers’ integrity as “fit and proper persons” at law.

He contends that the independence of lawyers is as important as that of judges. He argues that as an officer of the court, every lawyer should be a champion of justice, and be proud to be a worthy player in upholding and deepening the basic precepts of the rule of law and an independent judiciary.

According to Dingake, lawyers are bound to represent their clients without fear or favour. He maintains that once a lawyer has accepted instructions to represent a client, he or she must advance the case of the client without fear or favour. He writes that every lawyer has a duty to his client to fearlessly raise every issue, advance every argument, and ask every question, however uncomfortable, which might advance the case of the client. As an expert, a lawyer must not hesitate to advise a client that a case has weak legal legs and thus carries low prospects of success, if that be the lawyers’ considered opinion.

Reading this book, it became apparent that in addition to the above, a lawyer needs a lot of courage, as more often than not what he or she is instructed to do may offend vested interests or powerful people. Quoting the late Founding President of South Africa Nelson Mandela, who was also a lawyer, Dingake holds the considered view that courage is not the absence of fear but the ability to manage it.

He writes, almost passionately and authoritatively, that a lawyer’s first duty is to the court and not his or her client and that lawyers must always endeavour to promote the ultimate cause of justice by providing the court with the relevant law and facts required to resolve a matter correctly.

According to the judge, where a lawyer’s duty to the court conflicts with his or her duty to the client, the duty to the court takes precedence. He writes that through strict adherence to the highest ethical legal standards, lawyers can help ensure that the legal profession is trusted by the public and continues to be regarded as a “noble” profession.

In this book one also learns of the duty of prosecutors in a criminal trial. According to the judge, prosecutors are ministers of justice and must only prosecute if, on the face of it, there is enough evidence upon which a conviction is possible. Once a decision to prosecute has been taken, the prosecutor should disclose all relevant information to the accused. Dingake writes that no lawyer should lend their assistance and name to a prosecution that is unlikely to end in a conviction.

The book also discusses etiquette of lawyers. According to Dingake, etiquette is very important in the practice of law as it emphasises the importance of honesty, professionalism and civility. He says proper etiquette requires lawyers to be in friendly terms with each other despite representing different clients with opposing interests.

The judge says proper etiquette requires that a lawyer should resist the temptation to impugn the integrity of the court and the opposing lawyer when it becomes clear that he or she may be losing the case. The judge maintains that the most important rule of etiquette is to stand up when addressing the court and to always address the opposing lawyer, as “my learned friend”. This, Dingake says, makes it clear that the legal tussle is not personal.

Overall, this book is packed with so much information that lays bare the qualities of a good lawyer and how lawyers are expected to conduct themselves to preserve the honour of the profession. The book generally covers legal professional ethics and court etiquette relevant to the duty of a lawyer in the major legal systems of the world.

It emphasises the point that lawyers must not only practice their craft with absolute integrity, but should also be well behaved and civil to each other, the courts and other court users. The book is a treasure for lawyers especially trainee lawyers. I gladly join Justice Kirby in unreservedly recommending it to every lawyer, law student and members of the public.

*Moses Magadza is a multiple award-winning journalist and communication practitioner. He is a PhD student with research interests in framing, priming, agenda setting, propaganda theory, Critical Discourse Analysis (CDA) and the representation of Key Populations in the media.