Martin Endjala and Ester Mbathera

The Khwe and !Xun people, who reside in the Bwabwata National Park, shared by the Zambezi and Kavango East regions, often face the challenge of keeping their deceased loved ones in the villages for days.

This is because there are concerns that if burials take place without official notification, authorities might demand the exhumation of the bodies.

David Musamba, a San activist, highlighted how modern burial practices are threatening their cultural norms.

“We are told not to bury people without coffins anymore. The officials from the government told us that we will have to dig up the bodies if we bury the people our way,” he said.

The closest mortuary for these communities is at Andara District Hospital, about 100 km from most of the villages.

“Imagine having to carry a dead body to the road and ask a driver to help you transport it to Andara. Sometimes we get help from the game rangers. If you go through the process to obtain documentation and eventually the coffin, it takes a long time. Sometimes up to two months. What must we do in the meantime?” he questioned.

The conflict between San traditions and modern funeral practices began in 2003, when the government, through the Directorate of Marginalized Communities in the Ministry of Gender Equality, Poverty Eradication, and Social Welfare (MGEPESW), introduced a funeral assistance program for the San community.

“They said we are embarrassing the country with the way we bury our people. How is it a crime for us to be one with nature? We have buried our people in animal hides and now in blankets,” said Musamba.

This process is further complicated when the deceased person is undocumented.

“We first have to get them registered and get a death certificate before you apply for a coffin. This whole process requires money for one to travel from one office to another. That is why sometimes you will find bodies of San people in mortuaries because people give up and move on with their lives,” Musamba explained.

Rebekka Namwandi, deputy director of marginalised communities at MGEPESW, explains the government’s position.

“This is for registration purposes and a dead body cannot be buried without a death certificate. That’s why those processes are followed,” she said.

Namwadi said the ministry does not prevent people from observing their customs and norms but introduced the burial program to address the situation in Gobabis between 2003 and 2005 when 17 bodies remained in the mortuary for years due to unaffordable burial costs.

In 2007, the state mortuary at Gobabis Hospital conducted a mass burial for twelve unclaimed bodies of San people.

Those who were identified and their families were unable to cover funeral expenses and coffin costs.

“This programme was then developed to make sure that our people can be buried in a dignified manner and make sure families are able to collect the bodies of the deceased loved ones without hiccups,” Namwandi explained.

In response to the programme not being known to other communities and its tainted failure, Namwandi explained that as of January to date, its officials in all regions have been distributing food amongst other necessities to the marginalised communities every month.

“If the people are saying they don’t know. Our officials are in the field every day. I stand to be corrected to really know which village it is so we can assist these people,” she said.

She said the ministry continues to deliver on its mandate, including assistance with burials, food, and transportation for learners in boarding schools for families in need.

Former advisor to the president’s office on Indigenous people, Calvin Kazibe, provided insight into traditional San mourning and burial practices, stating that their customs are not about food, alcohol, or religious rituals.

“All we care about is paying our respects to Mother Nature, our ancestors, and burying our loved ones,” Kazibe said.

He recounted the custom of gathering around the fire, singing to their ancestors, and burying the wrapped body in a designated field the following day.

Former adviser to the president’s office of Indigenous people, Calvin Kazibe, explained that San people mourning and burials are not about food, alcohol or having religious rituals.

“We normally just gather around the fire during the evening when the person has passed on singing to our ancestors while the body is wrapped in a cloth, but now with modern culture, the body would be in a coffin. The next day the body would be buried in a field designated only for burials,” he narrated.

Kazibe explained that stones are put on graves not as markers but to prevent animals from digging up the body.

He noted that modernisation has negatively affected their way of life, particularly funerals, which now require assistance in purchasing coffins and transporting the deceased.

He also described how, traditionally, they did not hold funerals for the elderly or sick, who often passed away during long journeys in search of resources.

“The reason for this was because they used to move from one place to another, travelling long distances. They did not want to carry the old people or sick people, as this would further derail their journey in search of greener pastures. They only bury those that die while living with them,” he explained.

San communities do not announce deaths through newspapers, radio, or social media.

“The death notice was shared by word of mouth,” Kazibe said.

He explained how messengers were sent to spread the word to neighbouring homesteads to reduce the distance any one person had to travel.

“Once all relatives receive the message, they all travel immediately the same day to come and pay their respects and comfort the grieving family, followed by the burial the next day,” he said.

After the burial ceremony is completed, the mourners return to the homestead of the deceased, where they will overnight that day gather around the fire doing rituals to appease their ancestors.

They would depart the next day to their homesteads.

Kazibe acknowledged that post-mortems and extended stays in mortuaries have disrupted their cultural practices.

“We are left without a choice but to adapt to the new ways, which has become costly as many of our people are unemployed and cannot afford the modern ways of burials,” he said.

Should there be no funds to bury a San person who died in the care of the state, the minister of health and social services, Kalumbi Shangula, explained that the ministry does not bury bodies except for pauper burials.

“Bodies are collected and buried by family members irrespective of their backgrounds,” he explained.

Nampol national police spokesperson Deputy Commissioner Kauna Shikwambi said in all circumstances, when an autopsy is done, families ought to take the body from the police mortuaries unless they delay collection. “Regulations, policies, and laws are applicable to all,” she said.

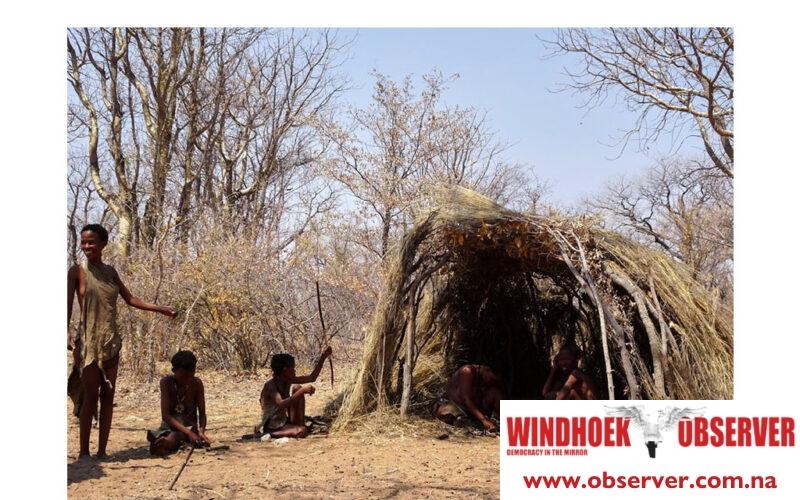

The San people, also known as the Bushmen, are indigenous hunters and gatherers of southern Africa, with ancestral territories spanning Botswana, Namibia, Angola, Zambia, Zimbabwe, Lesotho, and South Africa.

They are considered one of the oldest surviving cultures in the region.